The casino industry has evolved a lot since the Mirage’s transformational debut in 1989, but resorts still have room to grow to keep up with today’s customers.

That was one of the key messages delivered during a series of public discussions held Tuesday at the Mirage as part of a major weeklong academic conference on gambling-related issues.

It came up at various points throughout the first full day of the 16th International Conference on Gambling & Risk Taking, when industry and academic leaders weighed in on the past, present and future state of the so-called integrated resort model.

Held once every three years, the last version of the conference took place at Caesars Palace. Organizers chose the Mirage this time because the resort had turned 25 years old since the last time the gathering was held, according to Bo Bernhard, executive director of UNLV’s International Gaming Institute, which organized the conference.

That milestone was of great significance in Bernhard’s eyes, because he said that when the Mirage opened, “it changed everything.”

“It transformed the product and the way in which it was consumed,” he said at the beginning of the day. “It directed attention away from the gambling act for the first time.”

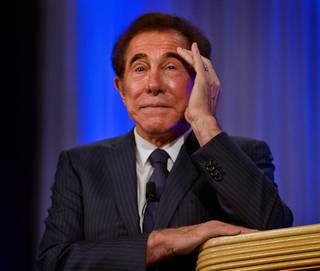

Accordingly, casino mogul Steve Wynn, who developed the Mirage, started the historical part of the day in his morning keynote address. The numerous subject areas covered by Wynn included not only the importance of nongambling revenue, but also some of his personal perspective on how his vision for the Mirage came about.

And he almost made it sound like it was easy.

Wynn said that one day, he parked his “little Mercedes, two-seater convertible” at the Sands hotel, where he stared at the nearby property he had recently purchased: the Castaways, which was located on the site that would eventually become part of the Mirage. Thinking partly about the film “South Pacific,” Wynn said he was inspired by the notion of a tropical resort on the Strip because “that’s not supposed to be here.”

He said the Mirage’s opening to the tune of some $630 million, and its ensuing financial success, proved that amount of money could be spent safely in Las Vegas.

But it wasn’t the casino floor that attracted customers, Wynn said — it was the other, more creative aspects of the resort. For the Mirage, that included an erupting fake volcano, a domed glass atrium with vegetation inside, a Siegfried and Roy show and a dolphin habitat.

“The idea behind it is as simple as sunshine in the morning,” Wynn said. “It’s the noncasino thing that is the driver. There is no dynamism to a casino — they are passive places.”

Later in the day, the conference conversation advanced to the present day when six experts — each representing a different continent — spoke about integrated resorts in their parts of the world. They showed how integrated resorts have taken shape across the globe, and the unique challenges presented in each area.

One of the locations, naturally, was Macau. The special administrative region of China years ago surpassed Las Vegas in its annual gaming revenue, and developers are continuing to build big resorts there.

Las Vegas-based casino operators are among those: Wynn Resorts Ltd.’s $4.1 billion Wynn Palace is expected to open later this year, as is Las Vegas Sands Corp.’s $2.7 billion Parisian. MGM Resorts International’s $3 billion MGM Cotai should open next year.

The ongoing development activity comes despite two years of declines in monthly gaming revenue. Davis Fong of the University of Macau said that while the Chinese gambling hub once raked in some $4.8 billion in monthly gaming revenue, that figure is now closer to $2.4 billion.

But Fong was optimistic that the worst of Macau’s gaming revenue decline was over. The downturn has reportedly been driven by a government-led crackdown on corruption that hurt business from high rollers.

Fong said Macau’s future lies in repositioning itself beyond gambling, aiming to become “the true world tourism and leisure center.” Bernhard later said that Macau appeared to be “Las Vegas-izing” in terms of the levels of nongaming spending from customers there.

Even generally in North America outside Las Vegas, casino development has changed over the years, according to Kahlil Philander of the British Columbia Lottery Corporation. With the casino industry now expanded across the continent, Philander said resort developers are focusing on urban areas instead of more remote spots, noting Wynn’s proposed resort near Boston and another project in Vancouver as examples.

“Now, they’re moving into these urban environments where, all of a sudden, you’re not dealing with a 50,000-person town … you have to get 2 million people to all agree to let the facility in there,” he said.

Later on, the conference moved into the future of integrated resorts with a panel on innovations and reinventions within the industry. There, the conversation lingered on two oft-discussed areas: technology and young people.

UNLV hospitality lab director Robert Rippee talked a bit about robots, which he said are already having an impact on resorts — he even demonstrated one that he said can deliver items to guests. And he envisioned a future in which robotics only plays a larger role in hotel operations.

Rippee also talked a lot about millennials, whom he characterized as a younger, more digitally immersed and social generation than the ones who came before them. As they continue to age, Rippee suggested that resorts focus more on creating experiences that will appeal to the millennial customer, even if that means changing the way casino spaces are typically conceptualized.

Rippee said the so-called integrated resort could go a step further by blurring the separations among its gambling, entertainment and other areas. By way of example, he pointed to large festivals such as Electric Daisy Carnival, which he described as having “music, art, food, retail — all thrown together … and you’re immersed in all of it simultaneously.”

“Their world is a mash-up experience. It all happens hyperconnected, and it’s all happening at the same time,” Rippee said of younger customers. “The integrated resort is the sum of all of the experiences put together at the same time.”

Rippee’s UNLV colleague Mark Yoseloff, executive director of the university’s Center for Gaming Innovation, looked at the same issue from a game-focused perspective. After going through a number of key milestones in gambling product history, Yoseloff said gambling was in great need of another groundbreaking moment.

Yoseloff said the creation of new areas — such as slot machines and electronic table games — has historically broadened audience for gambling. But gambling has not seen a new category or “meaningful innovation in an existing category” for at least a decade, he said.

“This is not about millennials. It’s not about knitting grannies. It’s not about left-handed Baby Boomers. It’s not about any single group,” Yoseloff said.

In Nevada, regulators and industry leaders have already tried to make progress in that area with new rules designed to usher in casino games that are more like arcade or video games. Yoseloff said there’s an opportunity to make skill-based games that “appeal to the intellect a little” by offering puzzle games, for instance.

Discussions about technology and young people, among numerous other gambling topics, should continue as the conference progresses. It lasts through Friday afternoon.