Some reports last month indicated the UFC may be sold for $4.2 billion. While officials of the local mixed martial arts promotion have disputed those stories, the asking price reveals what was long known: UFC officials have transformed the organization into one of the world's most valuable sports franchises.

In 2001, brothers Frank III and Lorenzo Fertitta purchased it for $2 million, which was considered a risk because the league was largely unregulated and lacked mainstream popularity.

What a difference a decade and a half makes.

UFC 200 Saturday at T-Mobile Arena anchors International Fight Week, a weeklong celebration of the sport with everything from multiple fight cards, a fan expo, meet-and-greet sessions and pool parties. All 50 states now sanction mixed martial arts, and the sport is so mainstream that it leads national highlight shows on fight night.

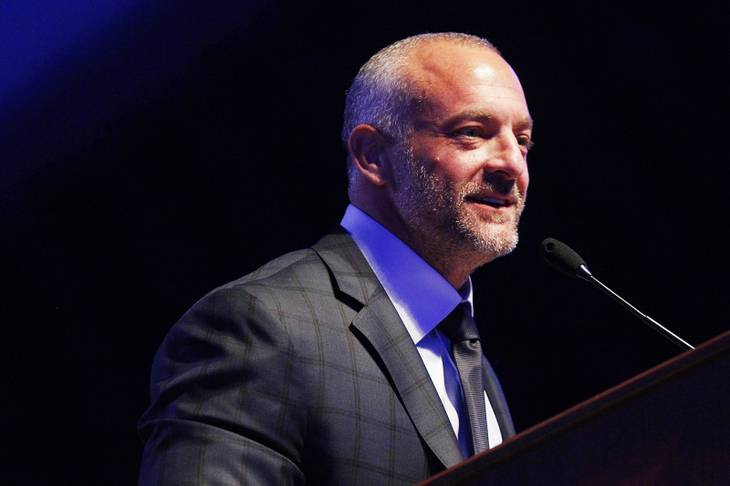

“Mixed martial arts and fighting in general may be the only sport that literally translates around the world, regardless of what country you’re from, what culture you’re from, what language you speak or what color you are,” Lorenzo Fertitta said in an interview with the Sun. “What we’ve been able to do that nobody else has been able to do is really organize combat sports around a brand.”

The UFC has grown from less than 50 fighters from five countries in 2001 to more than 500 fighters representing more than 30 countries. Five years ago, the organization signed a 7-year, $700 million contract with News Corp’s Fox Media Group. In 2015, UFC generated a record $600 million in total revenue, Lorenzo Fertitta said, and is now available to more than 100 million pay per view customers across more than 150 countries and territories worldwide.

Fertitta wouldn’t comment on the rumored sale, but instead focused on UFC’s past and the organization’s growth. The original founders, businessman Art Davie, Jiu-Jitsu Grand Master Rorion Gracie and TV executive Campbell McLaren, brought the concept to life in 1993.

It all started with Davie’s idea of a “war of the worlds,” which came from a desire to find the planet’s best fighter, he said last month. Gracie and McLaren, who had already worked together selling Gracie’s Jiu-Jitsu videos, came on board to run the new league. Joining the three was Semaphore Entertainment Group producer Bob Meyrowitz, who stayed through UFC’s sale to the Fertittas’ Zuffa LLC.

Meyrowitz declined to comment for the story, but McLaren described the organization’s first events as “a real life Mortal Kombat,” where kickboxers would fight Jiu-Jitsu masters, karate kings would square off against sumo-wrestlers and everything in-between. The only rules were no biting or eye-gouging.

The “spectacle,” McLaren said of the new league, whose goal was to find the world’s most effective style of fighting, was having each fighter dressed in their respective fighting garb practicing their own style of combat.

“We quickly saw that when a sumo looked like a sumo, when a karate fighter was wearing karate pants, that there’d be a huge visual appeal,” McLaren said. “It was like nothing that had ever been on television before and everybody wanted to watch it.”

With bare-knuckle boxing banned in most states at the time, the UFC founders decided on McNichols Sports Arena in Denver to host their first event, a major venue in the only state without a state athletic commission sanctioning bare-knuckle combat sports. UFC 1 drew over 88,000 pay-per-view buys out of about 33 million North American homes with pay-per-view capability. The next event, UFC 2, also held in Denver, on March 11, 1994, drew 300,000 pay-per-view buys.

“There was an audience waiting for something like this,” Davie said, “And the media was so stunned by it, calling it ‘the end of western civilization.’ Well that made everybody want to watch it.”

Added Gracie, “It created a whole new industry and inspired thousands of new fighters’ dreams.”

The momentum lasted for the better part of the next three years, thanks to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu fighter Royce Gracie and American wrestler Ken Shamrock, who quickly became the league’s most popular figures, and had a “robust” rivalry, Davie said. Others stars like American wrestlers Dan Severn and Don Frye emerged in the mid 1990s, and the sport seemed to have found its audience.

But before long, the spectacle began fading, thanks to political and public pressure. McLaren and Davie pointed at U.S. Senator John McCain, who called UFC “human cockfighting” in 1996, as part of his initiative to establish a national boxing commission.

McCain, a boxer during his time in the U.S. Navy, feared continued growth of the UFC, which was regularly bringing in pay-per-view audiences of 200,000 to 300,000, was taking away from boxing’s audience, McLaren said. The Senator from Arizona also wrote a letter to governors of every state asking them to ban MMA fighting.

Months later, in response to public backlash, Time Warner banned pay-per-view sales of the UFC in 1997, a move Davie called “a major setback.” While McCain’s criticism of the organization helped sell extra pay per views to rebellious UFC fans, Davie said the Time Warner blackout erased 75 percent of the organization’s revenue stream at the time.

“That was a killer,” he said. “It went from being widely-available to only available on a few satellite stations.”

Hurt by its political reputation and TV blackout, UFC was pushed into the underground scene, its founders said, and was nearing bankruptcy when Zuffa bought it just after the turn of the new millennium. With the economy in a slight recession, the Fertittas and minority owner Dana White began UFC’s turnaround from Day 1, driven by the goal of building the organization into a global business, based in Las Vegas.

“We saw the ability to really have a much broader reach, and that’s what we focused on,” Fertitta said.

Semaphore drew just 1,400 fans for Tokyo-based UFC 29 in December 2000, the organization’s last fight under its founding owners. Nine months later, UFC 33 at the Mandalay Bay Events Center drew nearly 10,000 fans and 75,000 pay-per-view buys in its Las Vegas debut under Zuffa ownership.

Since then, the league has averaged over 200,000 pay-per-view buys per fight, and has drawn as many as 1.6 million buys for its most popular event to date, UFC 100, in 2009.

Its next three most popular pay-per-view events were UFC 196 in March, UFC 194 in December and UFC 193 in November, where the events brought in 1.5 million, 1.2 million and 1.1 million pay-per-view watchers, respectively, according to statistics site MMAPayout.com.

Fertitta’s secret? Promoting “homegrown heroes” from different countries, who also resonate with international fans. He pointed out Conor McGregor, an Ireland native whose “meteoric rise” was embraced not only in Ireland, but by fans across the world.

“The country literally shuts down every time he fights,” Fertitta said. “But also in the 33 million Americans with Irish descent, and everywhere around the world where people believe they have one drop of Irish blood in them.”

Other international “heroes” include Brazilian fighters Anderson Silva and Jose Aldo and current men’s middleweight champion Michael Bisping, a native of Manchester, England, Fertitta said.

While the UFC increased steadily in popularity throughout the 2000s, Fertitta said the organization’s “greatest” growth came with the addition of Ronda Rousey and the women’s bantamweight division in 2012. Rousey, a Venice, Calif. native and the UFC’s first female fighter, defeated Liz Carmouche in the division’s first fight in UFC 157 on February 23, 2013.

Rousey entered the UFC alongside 11 other females, with the number having now ballooned to 59 fighters three years later across the bantamweight and strawweight divisions.

With both Rousey and McGregor undefeated through last November, the UFC pulled in record revenue. And while both have since lost, Fertitta said their losses “in no way” affect the UFC’s business model.

“Our business is built on the fact when consumers tune into the UFC, they get a matchup between top fighters, and that fighters aren’t matched to win,” he said. “It’s like the NFL in the sense that it’s impossible to go undefeated for 10 years straight. We think our fans look past wins or losses and just look forward to the best matchups at all times.”

Beyond the success of the women’s division and the UFC’s international outreach, Fertitta, a Las Vegas native, told the Sun one of his biggest pride points comes from the organization’s location, here in his hometown. UFC also has offices in Sao Paulo, Brazil, London, Toronto, Singapore and now Beijing.

Without mentioning a possible sale, Fertitta described a three-year plan that includes reaching “more fighters” in “more markets across the world,” for the ultimate benefit of both the UFC and Las Vegas.

Beyond pay-per-view buys, international stars bring “massive tourism” to the Las Vegas economy, he said.

“We see the effect when other fighters come from major countries come to Las Vegas, their fans fill the hotel rooms and spend the money, so developing nearby markets is crucial for us.”

The UFC co-founder said future “heroes” will come from Latin American countries, especially Mexico and Argentina, where the organization is focusing new developmental programs and this year’s edition of “The Ultimate Fighter: Latin America” reality TV show. He singled out “dynamic, young and talented” Mexican fighter Yair Rodriguez, who, at 23-years-old, is undefeated through four UFC fights.

Fertitta also mentioned China as a prime destination for developing international talent, saying he hopes to soon find the, “Yao Ming of fighting.”

After averaging just over 18 annual fights in its first 12 years since Zuffa bought the organization, the UFC posted a combined 87 fights in 2014 and 2015. UFC is on pace for another 40 events this year.

But despite its continuing growth, Fertitta said the UFC won’t be looking to one day host daily fights in Las Vegas, or even pass its recent average of just over 40 annual fights. Instead, he points to marquee fights and annual events, like the three-day UFC International Fight Week, which culminates this year with UFC 200, as items that “keep up with demand.”

International Fight Week, which features a Fight Night event on July 7, the conclusion of “The Ultimate Fighter” on July 8 and UFC 200 on July 9, also includes a three-day fan expo at the Las Vegas Convention Center with the organization’s biggest names signing autographs and taking pictures with fans. The event brought in an estimated $230 million to the Las Vegas economy last year, according to Fertitta and Brian Gordon, a consultant with economic research firm Applied Analysis.

“We’re a global brand, but Las Vegas is the main beneficiary,” Fertitta said. “We’ll always bring our most significant events here.”

Fertitta said he sees “no reason” not to keep the UFC in Las Vegas, calling the city a “global destination” and the league’s presence in the valley “a point of pride.” In January, the organization began construction on a 184,000 square foot UFC Athlete Health and Performance Center, a 15-month construction project which will include sports medicine and science facilities and a performance gym for fighters to train and rehab year-round.

“Instead of sending fighters to California, to New Mexico, to Texas or Florida, we want them to come here to get the best training, physical rehabilitation or whatever it might be,” he said. “We want everything to be right here, in Las Vegas.”