A decade ago, when business was booming in Las Vegas and tourists flooded the Strip with cash, developers seemed destined to pull in record profits with each new multibillion-dollar project they announced.

America’s zeal for spending and fun, coupled with consumers’ disposable income, fortified builders’ confidence. Many inked absurd deals to gain a foothold in Las Vegas’ real estate market.

Some paid as much as $34 million for a single acre of land.

Everybody wanted a piece of the action, and players with the deepest pockets paid whatever it took to get in. Analysts called the phenomenon “punch-drunk capital.”

“That’s the sound bite we used to have around here,” said Joshua Smith, an analyst with Colliers International Gaming Group.

Analysts rarely utter the term anymore. The city’s winning streak ended when the recession hit.

Developers began to wise up and focus on a more realistic bottom line.

As CityCenter struggled and construction on Fontainebleau and Echelon stalled, developers abandoned the illusion that business on the Strip would always improve.

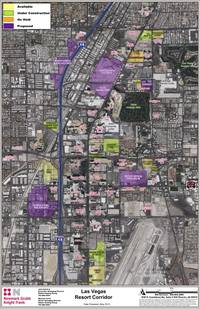

Strip land values reflect that change in attitude.

Today, resort corridor real estate sells for 80 percent less than its peak value. An acre of prime Strip land typically goes for $3 million to $6 million.

The stratospheric drop was highlighted by the sale of the failed Echelon earlier this year. Malaysian powerhouse Genting Group paid Boyd Gaming $350 million for the 87-acre site, about $4 million an acre.

By comparison, the El-Ad Group paid Phil Ruffin $1.2 billion for the New Frontier in 2007, or $34 million an acre.

For Ruffin, it was the deal of a lifetime. He spent $142 million for the 26-acre casino in 1998.

The deal marked the largest price-per-acre land sale in Strip history.

While no newer sales compare, Strip real estate had a strong showing through most of the 2000s.

In December 2005, Harrah’s Entertainment, now Caesars Entertainment, acquired the Imperial Palace from the Ralph Engelstad and Betty Engelstad Trust for $370 million, or roughly $20 million an acre. Ralph Engelstad opened the resort in 1979. Caesars has since rebranded it as the Quad.

In early 2006, Columbia Sussex bought the 34-acre Tropicana from Aztar Corp. for $30 million an acre. It later lost the casino to bankruptcy.

Harrah’s struck again the same year, snatching up the former Westward Ho for $279 million, or $18.4 million an acre. A year later, the gaming giant later traded the 15.1-acre property with Boyd Gaming for the 4.5-acre Barbary Coast, which became Bill’s Gamblin’ Hall and now the Gansevoort. The Westward Ho sat adjacent to the site of Boyd’s planned Echelon, while the Barbary Coast neighbored the Flamingo.

In May 2007, MGM Resorts International bought a vacant 26-acre parcel at the corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and Sahara Avenue for $444 million, or approximately $17 million per acre. To date, MGM has done nothing with the land.

Later in 2007, SBE Entertainment bought the Sahara for an estimated $19 million an acre. The parcel will soon be home to the SLS.

That was one of the last big Strip deals before the crash.

“In the old days, people were looking for return, but they just thought it was a guarantee: If I built something on the Strip, I’d absolutely make money,” said John Stater, research director of Colliers International.

Stater now shrugs at what he calls developers’ “irrational exuberance.”

It’s the same fervor that motivated people to cash in their life savings to try to flip a house for a massive profit, only to lose the properties to the bank, he said.

“Every single peak, whether it’s Dutch tulips or land in Vegas, comes down to irrational exuberance,” Stater said. “More and more people want it, which drives the price higher. But nobody has that money, so they have to start taking out loans, and the loans get bigger and bigger, and eventually it gets tougher and tougher” to reap a return.

During the boom years, developers banked on making more money in every coming quarter than during the last.

When the bottom fell out, their lone goal became to stop the bleeding.

The next major Strip sale didn’t come until 2010 when developer Brett Torino and a duo of secret partners bought 2.15 acres at Harmon Avenue and Las Vegas Boulevard for $25 million, or $11.6 million an acre. The dramatic drop in price reflected developers’ shift in strategy — and confidence.

“People went back to real estate fundamentals,” Smith said. “They hit a massive reset button.”

Developers today are testing the waters but have yet to dive headfirst again into the Strip real estate game.

“People come into this town every day to do feasibility studies to find out what will work and what pockets are growing the fastest,” Smith said.

Most are reluctant to dump truckloads of cash into new projects. The bulldozer model of building — knocking down existing structures to build anew — has all but disappeared.

The new model is redevelopment. Developers with projects underway have resumed construction that was mothballed during the recession or embarked on renovations. Facelifts are cheaper than building from the ground up.

“Look at the SLS and the Quad,” Stater said. “They didn’t knock anything down. They’re renovating. Ten years ago, we were tearing them down and starting from scratch.”

Most sellers, on the other hand, are holding out for a total recovery. Strip listings haven’t flooded the market.

“It’s like if you buy stock, and it’s down 50 percent,” said Chad Beynon, an analyst with Macquarie Securities. “You wonder, ‘Should I sell it right now?’”

Even so, certain Strip parcels will always carry a hefty price tag.

John Knott, executive vice president of Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, calls them “hard corners.” They are sites near busy intersections that typically sell for $25 million an acre or more.

Peterson Properties last year sold a Walgreens on a 0.66-acre plot in front of the Palazzo for $71 million. When developer Steve Johnson bought the land in 2003, he spent $34 million, or $50.8 million an acre. There also are condos stacked on top the store, both of which generate huge returns.

The Peterson deal was one of the biggest of 2012.

“That turned out to be a great investment,” Knott said. “They have a variety of uses that could extract value.”

It also points to the potential of mixed-use property on the Strip.

Caesars Entertainment jumped at the concept in 2011 when it announced its $550 million Linq development, a hodgepodge promenade of entertainment, retail and dining. MGM Resorts jumped on the bandwagon with its $100 million plan to update the walkway between the Monte Carlo and New York-New York with a park, food trucks and shops.

Part of developers’ hesitance in building big and new comes from MGM’s experience with CityCenter. The complex gained steam just as the recession took hold, and the economic collapse nearly bankrupt the project.

Costs ballooned from $4 billion to $10 billion. Critics called it a failure and dubbed it a “Tower of Babel.”

Once it opened in 2009, it took MGM almost four years to recover. The company realized a less than 5 percent return on its investment, when the goal typically is 15 percent to 30 percent. It finally began profiting in early 2013.

“The industry learned its lesson,” Beynon said. “There isn’t interest in blowing up properties and spending billions.”

Will the market ever return to its peak performance?

Predictions vary depending on whom you ask.

Beynon isn’t sure.

“We don’t believe the market will get back to peak because of lower returns on investment and a reduced amount of foreign money,” Beynon said. “We expect prices to improve but not to the degree of pre-recessionary periods.” Others, however, are more optimistic.

Stater predicted the Strip will welcome another redevelopment boom. Knott also believes things will get better.

“I’m always amazed at how much this city changes,” Knott said. “We thrive on finding out what people want and delivering.”